By Jiazhen “ Joan” Chen

The Taxation System

The term tax serves as a firm reminder to people that they have been given personal and mandatory responsibility to divert a certain amount of their wealth—past, present, or future—to become part of the revenue required by institutions and units of government performing public services (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 114). All citizens owe taxes. The benefits of government services are shared by all of the nation’s citizens in varying degrees, depending on their needs. A good tax system provides that every person and every business be required to pay some tax to government (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 115).

Because everyone pays taxes, as a matter of simple justice and fairness, a good tax system distributes the burden it creates among all its citizens in an equitable manner. The notion of equity incorporates both horizontal and vertical dimensions. First, horizontal equity requires that those taxpayers in similar circumstances should be treated equally. Second, vertical equity requires that taxpayers in different circumstances should be treated according to those differences (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 115).

It is necessary for education to be financed by government, given its capability of collecting resources from the private sector and distributing them equitably among institutions in the public sector. Historically education has been financed largely at the local level. In the opinion of many, this fact creates one of the more difficult problems with which educators must concern themselves—providing equitable school programs and creating equitable tax burdens across the state within the framework of the local property tax system (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 116).

The Five Basic Criteria For a Good Tax System

- Equity and Ability-to-Pay

Whether a tax system is fair depends on how it treats all individuals, particularly the rich and the poor. If the greatest percentage of the tax burden falls on low-income individuals, then the tax is regressive and considered unfair. Taxes are considered fair if they contain features of progressivity with the largest percentage falling on individuals with higher incomes system (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 117).

- Adequacy of Yield

Maintenance of the extensive services of government requires large amounts of tax revenue. Therefore, it is important that taxes be applied to productive sources. There is no point in complicating the system by the addition of taxes that have little individual potential for yielding revenue in substantial amounts (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 117).

- Cost of Collection

To the extent possible, taxes should have relatively low collection and administrative costs for both the government and the individual. Government institutions are interested in the amount of net revenue available to them rather than the gross amount of dollars collected (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 117).

- Predictability and Stability

Governments depend on taxes for funding; consequently, revenues that are consistent, dependable are preferred to those that change from year to year. The predictability of consistent or stable revenue streams allow governments to forecast future income and expenditures with some accuracy and assure that revenues will be available to meet their needs (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 118).

- Difficulty to Evade

It is a distinct violation of good taxation theory to pass tax laws that have gaping loopholes whereby many citizens or businesses can escape paying their share of the tax burden. Such unfair exclusions make those who contribute pay more than their fair share of the costs of government services (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 115).

Different Types of Taxes

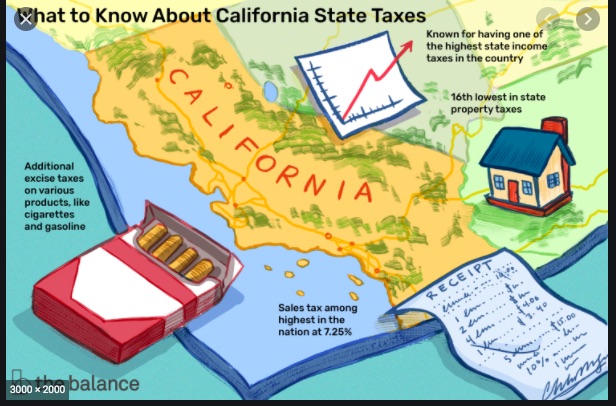

Property Tax

A property tax is levied against the owner of real or personal property for individuals and businesses. Real property is not readily movable; it includes land, buildings, and improvements. It is usually classified as residential, industrial, agricultural, commercial, or unused (vacant). Personal property is movable; it consists of tangibles (such as machinery, livestock, crops, automobiles, jewelry and recreational vehicles) and intangibles (such as money, stocks, and bonds) (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 130).

Income Tax

The personal income tax is usually a progressive tax levied on the income of a person received during the period of one year. It is the basis of the federal financial structure, but is also used to a lesser degree by nearly all of the states as a funding source (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 127). Individual income is derived from salaries, dividends, sale of assets, interest, and gains. There are both individual and corporate income taxes (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134).

Sales Tax

A sales tax is a levy imposed on the selling price of certain goods and services. It is generally applied at the retail level rather than on wholesale operations. If food and other necessities are subject to a sales tax, the tax becomes regressive. The sales tax is used most often at the state level of government although it is sometimes applied at the county and city levels. It produces large amounts of revenue and is one of the most transparent ways to collect taxes, but its use without exclusion of necessary goods and services tends to overburden poor families (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 129).

Excise Tax

An excise tax, also called a sumptuary tax, is sometimes imposed by government with the primary purpose of helping to regulate or control a certain activity or practice not deemed to be in the public interest (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134).

Severance Tax

Severance taxes are defined by the Department of Commerce as “taxes imposed distinctively on removal of natural products—e.g., oil, gas, other minerals, timber, fish, etc.—from land or water and measured by value or quantity of products removed or sold.” This tax is imposed at the time the mineral or other product is extracted (severed) from the earth. Levies can also be made for the privilege of removing a given commodity from the ground or from water. These levies are sometimes called production, conservation, or mine (or mining), and occupation taxes (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134).

Evaluation Table of the Tax System in California

| Stable | Easy to Collect | Equitable | Adequate | Easy to Evade | |

| Property Tax | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Income Tax | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sales Tax | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Excise Tax | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Severance Tax | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Highest-ranked Tax

Income tax ranks highest becauseincome is a good measure of an individual’s economic well-being or “ability” to pay. Using income as a measure of fiscal capacity creates a fair system of tax burdens on society. Equals—those persons with similar incomes—are taxed equally. Unequals—those persons with different incomes—are taxed differently. As the cornerstone of the tax system, all other taxes are assessed in relation to the impact they have on a person’s income (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134).

An advantage of using income as a measure of economic well-being is that it can be measured and taxed over a specific period of time. If it fluctuates, so does the tax that is paid. Income is also relatively easy to track, although sometimes it can be hidden in the form of tips, trades, or exchanges. Another advantage is that all taxes are paid out of income (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134). Income taxes provide a substantial yield, making it a key approach in funding government programs and services (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 129).

Lowest-ranked Tax

Excise tax ranks lowest because for this kind of tax, the collection of revenue is only a secondary purpose of the tax. Thus, funding is usually comparatively small, and there is little room for expansion or extension of the tax (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134). In general, sumptuary taxation receives little support from tax theorists. The fact that sumptuary taxes do, in fact, produce revenue often leads to a situation in which a governmental unit in need of funds is tacitly encouraging an activity which tax legislation sought to discourage (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 134).

Best Tax for Education

Property tax is the best tax for education because of its desirable traits. It operates as a direct tax. It is easily collected. It is almost impossible to avoid paying. It is highly productive. It is highly visible. It is relatively stable and can provide a reliable source of revenue. It is regulated and controlled by local boards of education within state law (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 130-131).

Property taxes were the first kind of school taxes, and they still constitute almost the complete local tax revenue for schools. The states have long based their local school revenue systems on a property tax. For a long time, the property tax seemed to be reasonably satisfactory as an education financing mechanism. The property tax at the local level has proved to be a good and reliable source of revenue for operating schools and providing many other services of city, town, and county government (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 130).

Equity and Adequacy Issues

Even though the property tax has served the schools well for many years, it has always faced some criticism. The property tax no longer represents the fair or equitable measure of taxpaying ability that it did years ago (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 131). The finance problems encountered by most urban centers illustrate some of the deficiencies of the property tax. Cities generally have higher percentages of high-cost students to educate—such as students with disabilities, low-income students and English language learners (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 132). Described by many as the most regressive, oppressive, and inequitable tax of all, it has lost much of its traditional popularity as a source of revenue for schools. Many segments of society—taxpayers, educators, and economists—have protested both its use and particularly its extension (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 132).

A single tax, regardless of its basic strengths or utility, can never be fair for all citizens of a taxing unit. Taxation theory requires diversification with a broad tax base—such as income, sales, and property—so that an individual’s “escape” from a particular kind of tax does not mean complete exemption from paying a tax of any kind. Diversification of taxes is important, but simplicity is equally necessary in any good tax system. Taxpayers cannot be expected to support intricate and complicated tax laws they cannot understand (Brimley, Verstegen, & Garfield, 2012, p. 116-117).

References

Brimley, V.R., Verstegen, D. A. & Garfield R.R. (2012). Financing education in a climate of change (12th edition). Pearson Education Inc.